Marcus Bourke - His G.A.A. Writing

Tipperary Historical Journal 2002, pp 13-32

Although it is the greatest sporting organisation in the country the Gaelic Athletic Association has a very slim library of publications to its credit. For a body over one hundred years in existence the list of books is anything but impressive. If one goes back to the period prior to the centenary of the association in 1984 the number of histories produced at national, provincial, county or club level was very small indeed. Since then clubs and counties have done much to have their histories written down. In the province of Munster approximately one hundred and forty club histories were written between centenary year and 2001 This may appear impressive and indicate a good effort at catching up until it is realised that seven hundred and thirty clubs affiliated in the province in millennium year! The number of these that had recorded their histories before 1984 was infinitesimal.

At the county level the picture isn't much different. Cork. Limerick and Tipperary are well served with county histories. The Mercier Press published a snapshot history of Clare in 1996. The Kerry story over the past thirty years has been well covered but the earlier history of the G.A.A. in the county has been neglected. Pat O'Shea, in his 1998 publication on the history of the Kerry county championships, has gone some way to rectifying the situation. The picture in other provinces is not greatly different. Six of the Ulster counties have county histories. The picture is poorest in Leinster where the Dublin county history is in the process of being written.

At the provincial level Munster produced a comprehensive history in 1984. It was updated in 2000 and it remains the only province with such a detailed account of its activities. Leinster produced a slim account of its history in 1984. The Connacht history is being written by a committee at the moment and I am not aware of anything being done in Ulster.

At the national level there are four publications that aspire to be histories of the association. The first was written by Thomas F. O'Sullivan in 1916 and published in Dublin. O'Sullivan was a former trustee and vice-president of the association, a former president of the Munster Council and a past secretary of the Kerry county board. The book was called the 'Story of the G.A.A.' and sub-titled 'First History of the Association'. It contained two hundred and forty pages and included one hundred and twenty illustrations. It sold for one shilling. It was promoted as a detailed, well-arranged and copiously illustrated history of the Gaelic Athletic Association.

The book is very rare today and seldom turns up in second-hand catalogues. However, it is possible to access it in a different way. The book is made up of a series of articles that first appeared as such in the Evening Telegraph, Dublin in October 1914 and, after twelve months, was continued by the Sunday Freeman and the Weekly Freeman. In the preface to the book the writer states that 'the articles were written without fee or reward, and their reproduction now is not a sound commercial speculation.' The reason why he still went ahead with the publication was to give 'the public an opportunity of appreciating the patriotic work which has been done during the past three decades to promote and develop Irish pastimes on self-respecting Irish lines’.

O'Sullivan goes on to inform his readers of the considerable labour and research he put into the preparation of the articles. His information was procured from official and unofficial sources. Files of newspapers were carefully read. Hundreds of Gaels in all parts of the country were consulted 'in order to clear up obscure points, correct errors, or procure some necessary information which could not be obtained from the existing official records.' He was proud of the illustrations carried in the work and regretted being unable to procure the photographs of a number of prominent contemporary Gaels.

He concludes by stating that he spared no effort in achieving accuracy in his work, and also that he made every effort to be scrupulously fair in the treatment of all contentious subjects. Apart from a few suggestions at the conclusion of the book on how the association could be improved, he states that otherwise 'I have contented myself with presenting the facts in their proper perspective, leaving my readers to draw their own conclusions.'

Without a doubt the book is a labour of love. The spirit and feelings of the writer are given expression in the introductory chapter. The G.A.A. 'has helped not only to develop Irish bone and muscle, but to foster a spirit of earnest nationality in the hearts of the rising generation, and it has been the means of saving thousands of young Irishmen from becoming mere West Britons.' In spite of all the turbulence the association suffered, in spite of the waves of vicissitudes it had to endure, in spite of the conflicts between the advanced Nationalists and the Constitutional party which almost rent it asunder, it survived because 'the basic principle on which it was established was sound and patriotic, and at no stage of its career was it entirely bereft of the services of earnest men who appreciated the tremendous potentialities of the organisation as an athletic body and a great national asset.'

The book starts off with a sketch of the founder of the G.A.A. in chapter 1 and O'Sullivan is unstinting in his appreciation of the founder: 'Only a great man could found such an organisation, and unquestionably Michael Cusack was great - great in earnest, self-sacrificing patriotism, and in all those qualities of head and heart that stamp the leader out from multitudinous mediocrity and give him a place apart.' The early chapters deal with the foundation of the association and the difficulties of the early years. He quotes extensively from contemporary documents and is good at listing the delegates present at the early conventions. In chapter XVIII he gives a detailed account of the first All-Ireland football and hurling championships and after that he devotes mostly a chapter to each year. The format of the chapters follows the same lines. For instance in chapter XXV he opens with the state of the association in 1890: 'The Association showed traces of decline in 1890.' He gives some reasons for same and outlines some important happenings in the association' not only in Ireland but abroad as well. He gives an account of Central Council meetings and resolutions proposed, and mentions prominent men in the workings of the association. Most of the chapter is then devoted to the hurling and football championships. He takes the history of the association up to 1908 in chapter XLVI. The following chapter is devoted to 'Games and Nationality' by Douglas Hyde in which he pleads with the latter for a closer union between the G.A.A. and the language movement.

The final chapter is devoted to a number of suggestions to Gaels by O'Sullivan. He would like to see players use the Gaelic language on Gaelic fields: 'Until they do they are failing in their duty towards our ancient tongue.' According to him every Gaelic club should be an Irish class, or form an important section of the local branch of the Gaelic League. A second suggestion is that medals should be abolished and books given to winners of hurling and football matches and athletic contests instead. He gives a list of patriotic and historical books to fill the bill. 'Books, not medals, will make our Gaels more earnest, intelligent and patriotic Irishmen, and on that ground should be more suitable as presentations in connection with Gaelic victories.' He also calls for the development of camogie and handball. Prior to the annual congress there should be a ceili or some other form of Irish-Ireland entertainment held in the Mansion House. As well as publishing the letters of Drs. Croke and Fennelly in the Rule Book of the association, he should also like to see the letters of Parnell, Davitt and John O'Leary. 'Why not also have the photos of the first four patrons in the book?' he adds. According to O'Sullivan there should be a Publication Committee appointed, who would be entrusted with a certain sum of money for the purpose of defending the association from attack or misrepresentation, and would provide interesting reading for its members. He was very concerned with the small amount of literature relating to the association. He exhorted county committees seriously to consider the publication of county histories. As well 'in districts such as many of those in Donegal which at present is not affiliated to the Ulster Council, money should be spent to establish clubs, and if necessary an Irish-speaking organiser appointed for the purpose.'

Thomas F. O'Sullivan's history is a very important work. It is a comprehensive account of the first quarter century of the Gaelic Athletic Association. It is an invaluable source for information on the early decades. It has the great quality of accuracy. An important authority on the period gives it an accuracy rating of ninety-eight percent and believes the remaining two percent is concerned mainly with omissions. It gathers within its covers much information that is accessible only through a tedious trawl of contemporary newspapers and other publications. Without it we would be in an impossible position for the early years of the association. In so far as any publication can be, the book is a model of impartiality. If you didn't know that O'Sullivan was a staunch IRB man you would find it difficult to glean the fact from its pages. We owe a great debt of gratitude to Thomas F. O'Sullivan.

The next book to be mentioned is a more modest effort. It takes up the story two years after O'Sullivan left off. Entitled 'Twenty Years of the G.A.A. 1910-1930', it was compiled by Phil O'Neill, who wrote under the pen name 'Sliabh Ruadh'. It is subtitled 'A History and Book of Reference for Gaels' and is undated.

In a short introduction O'Neill tells us that the work is not intended as a detailed history of the association. Rather the pages 'are a summary of the chief events in the history of our National Athletic Association both in the field and in the council chambers for the years 1910-1930, as well as being a record of its growth numerically and financially during the period.' He hoped his book would prove an arbiter in disputes between fellow-Gaels about players and match scores. Also that it 'will be appreciated by the Gaels of the countryside, as well as by those in the city clubs and colleges, and I further hope that its perusal will be an incentive to our younger generation to add by their actions, perhaps, another bright chapter or two to the future annals of our great organisation.'

Although stretching to over three hundred and sixty pages the work contains one-third fewer words than O'Sullivan's. Written in larger print with a lot of headlines in bold print, it reads more like a newspaper account of events. And that, essentially, is what the book is, a compendium of newspaper accounts from the Kilkenny Journal. It lacks the continuity and flow of O'Sullivan. To open a page at random gives the flavour of the work. On page 60 there are three headings: Leinster Football Final is a short account of six lines. It is followed by A Great Munster Final, which account extends to over thirty lines and includes the lineouts as well as some match details. The final heading is a short piece of five lines under Cardinal Agliardi Medals. Essentially a cut and paste job of newspaper accounts, it is, nonetheless, an important source of information on the period. O'Neill has collected much material together which, otherwise, one would need to go to the newspapers for. As well the work is much better on local events than O'Sullivan's. We get information on Cork county conventions, matches in Waterford, Thurles Gaelic Grounds, Ring Irish College, to quote at random. In most cases dates are given which are important references to have when one is looking for greater detail.

The book devotes a chapter to each year and uses an introductory chapter to give infonnation on 1909 and so link up with where O'Sullivan left off. There are a number of photographs, predominantly of Kilkenny and Tipperary G.AA personalities, and a number of contemporary ballads. Not as authoritative or comprehensive as O'Sullivan's, O'Neill's book is, nonetheless, a handy reference work on the first decades of the twentieth century.

The third book to be mentioned is Our Native Games by P. J. Devlin. It is a small work of a little over one hundred pages, is undated and was published by M. H. Gill and Son, Ltd., apparently in the mid-thirties. According to the author it is not an attempt to write a history of the association or to produce a chronicle of its past activities. 'My purpose is simply to envisage the conditions in Ireland when the Association was established fifty years ago; to examine the motives of its founders; to explain the void it filled in the lives of the people, and to make clear the aims which have become the essence of its existence and the secret of its popularity.'

Much of the material in the book had appeared from time to time in the pages of The Catholic Bulletin. The content is really concerned with the philosophy behind the Gaelic Athletic Association and the effect it has had on the improvement in the national spirit. According to him the influence of the revival of our games cannot be better illustrated than by the interest it aroused in a part of Ireland where distinctive games and pastimes had long been suppressed. 'In that corner of Ulster where I then had my being, life was drear and aimless during leisure hours, especially for the young. The older generations, if so disposed, as most of them were, had card-playing and, despite law and humanity, cock-fighting, for distractions; and, strange to relate, it was from devotees of the latter 'sport', who had penetrated to central counties, that I first heard of wayside jumping and weight-casting and rural team games.' The writing is hortatory. Devlin saw the history of the country in terms of a conflict between native and alien ideals and interests. He believed that peaceful penetration had become more destructive of nationality than open aggression. Sinister influences enticed men from the ranks of national endeavour so that 'a barrier had to be raised to protect the leal from the indifferent and secure the organisation against part-time use by those who can only have had a half-hearted attachment to its basic aims.'

According to Devlin the G.AA has no room for gladiatorial shows or subsidised competitions. 'If victory and trophies become the predominant pursuit, the chivalry that it is part of its purpose to foster, and the popular benefits it exists to provide, must disappear.'

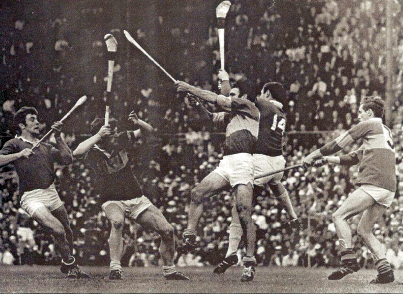

Many of his ideas would appear dated today. He is fascinated by the glamour and greatness of the game of hurling. It stirs a chord in native hearts that no other pastime can awaken. It is as distinctive as the National Emblem itself. He would like to see its history written down. Even though it has spread to distant parts of the world, he cannot see it becoming internationally organised. He gives two reasons for this conclusion: 'It must remain essentially national, and the adept hurler, like the ideal poet, is born not made. The true art of wielding the caman flourishes only where it has been traditional.' He would probably cast a cold eye on the many schemes currently in existence for the spread of the game in weaker counties.

Today the book is not much more than an interesting curiosity. It reflects the thinking in the mid-thirties when the country was in a stage of siege, physical and mental. There was the economic war with Britain as a result of the Land Annuities issue. There was the mental siege as Fianna Fail pursued an Irish-Ireland policy, a dream of self-sufficiency and sought to emphasise all things Irish to the detriment of all things English. This siege mentality also found expression in the censorship laws, which sought to protect the soul of Ireland from alien ideas and images that would tarnish it in any way. P. J. Devlin is fighting these battles in Our Native Games. He is brandishing our games as an instrument in the battle for the soul of Ireland. We find 'English domination' balanced against 'Irish sycophancy'. For him the leaning towards imported pastimes is due to the desire 'born of serfdom and all its venalities, to ape and pose as a superior caste.' 'The small soul cowers in the presence of a dominant personality.' And there's much more of the rousing stuff of the political and cultural battles of the thirties but very little of value to the student of the G.A.A. today.

In 1958 the G.A.A. set up a History Committee (An Coiste Staire) with a brief to write the history of the association. The first man chosen to write the history was P;draig Puirseal. A Mooncoin, Co. Kilkenny man, he turned to journalism with the Irish Independent after completing an M.A. in English literature at UC.D in 1937. He wrote the first of four novels in 1942 and seemed destined for a literary career. However, he forsook novel-writing for sports journalism and founded The Gaelic Sportsman in 1950. Three years later he joined the Irish Press and was still on the staff of that paper when he died, after a brief illness, in 1979.

After some time disagreements arose between An Coiste Stair and Puirseal about the type of history he intended to write. The committee were looking for a work, which would be as factual as could be ascertained from reliable sources and be mostly free from anecdotes and hearsay. The writer, with his background in imaginative literature, was inclined to a more colourful and readable account of the history of the association. There was a conflict of intention and this led to a parting of the ways.

I understand the Purcell family were disappointed with the termination of his brief. His death came rather prematurely in 1979 and his sister, Mary, the novelist, collected his writings and had them published under the title The G.A.A. in its Time in 1982. The book contained a Foreward by Sean 0’Siochain, who retired as Director General of the G.A.A. in 1979. In the course of it, 0’Siochain gives us an idea of the kind of history of the G.A.A. Puirseal might have written had he been retained to do so by An Coiste Stair. 'It is an unusual book in that it is the product of three aspects of the author's ability: the capacity to relate the Athletic and Games Movement, as it developed, to the historical background of the time; the journalistic training which makes a milestone of every final; and the impressionable mind - filled to overflowing with anecdotes, incidents and colourful heroes - of the man who, from boyhood, was steeped in the G.A.A. tradition.

The next choice of An Coiste Stair was Thomas P. O'Neill, Professor of English at University College, Dublin. He had completed the biography of Eamon de Valera with the Earl of Longford and was keen on the task. But, he was a very busy man and in spite of many meetings with the committee, no work was forthcoming. Eventually he was given an ultimatum to deliver or be replaced. He pleaded for time, as he was anxious to do it, but was, in the end, replaced.

The third man to be chosen was Marcus de Búrca from Dublin. His qualifications were impeccable. Educated at Belvedere College, he graduated in economics and law from U.C.D. and King's Inn. During the 1950s he was a journalist and a practising barrister, and from 1960 he was on the staff of the Attorney General's Office as a parliamentary draftsman. As the author of two historical biographies, The O'Rahilly and John O'Leary he had become interested in the early history of the G.A.A. He had a methodical and business-like approach to his work.

In the Preface to the book de Búrca tells us he didn't come to the book as a total stranger to the G.A.A.: 'Like many hundreds of thousands of Irish men and women in the past century, I grew up in a home where Gaelic games were enthusiastically supported. However, apart from a brief period as an obscure player in my late teens, I have never been actively involved in G.A.A. and am not blind to its weaknesses and faults.'

Also his antecedents were perfect. His father, Pádraig de Búrca was a distinguished presence at Central Council meetings, an ex-officio member by virtue of being legal advisor to the association. His grandfather, John J. Bourke from Tipperary Town, better known all over Munster as 'Bourke the Handicapper', was an official handicapper and judge at athletic meetings in the early days of the association. The title of the completed work, The G.A.A.: A History, is probably indicative of the nature of the work. It wasn't the official history of the association but rather a commissioned work in which the author was allowed freedom of opinion.

De Búrca informs us on this opinion in the Preface: 'At the highest level in the Association I was assured that, while its records would be freely available to me, what was being looked for was my story of the G.A.A. and particularly of its role in the national movement of the pre-1922 era. All that was expected of me until my manuscript was completed was that I report progress periodically to the Committee. I was promised complete freedom both to use the records of the Association and to express my opinion of it: this promise has been scrupulously kept. For everything in this History, whether of a factual nature or otherwise, I alone am responsible.'

Journalists, who were present at the launch of the book at the Gresham Hotel in Dublin, on November 10, 1980, honed in on the question of the nature of the history. Paddy Downey of the Irish Times was critical of the way G.A.A. officialdom distanced itself from the history. According to him 'Successive speakers, all of them officials, past and present, of the G.A.A., seemed to distance themselves from the work. This, they implied, was not the official history of the association: it was one man's view and interpretation, that of Marcus de Búrca.'

Downey contended that the launching of the History deserved a glittering occasion: 'the G.A.A. is almost one hundred years old and up until now there has been no definitive account, no history, of an organisation which controls not only the activities of hurling and Gaelic football but represents one of the greatest, probably the greatest, social movements that this country has known.'

The attitude of G.A.A. officials to the launch of a history may have been due to a slight nervousness at the exposure of the association to the first full-length account of its activities. According to Liam Kelly, in a review of the book, xxviii the G.A.A. 'has nothing to be ashamed of here. Mr. De Búrca has given a realistic and honest account of the G.A.A. to the best of his ability. It's well-written and well-researched and documented. Some of the G.A.A.' s mistakes and embarrassments are included. That may not suit some people who would wish to read a glowing eulogy without any hint of fault or mistake. But it's all the more realistic and truthful for that. '

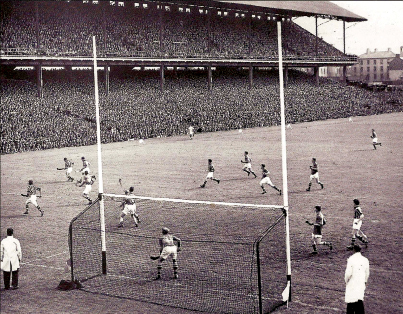

Kelly continues: 'Hardly a ball is kicked or a sliotar struck and few of the greats of Gaelic games get a mention in Marcus de Búrca's 'The G.A.A.: A History'. The excitement of the big day, the experience of Croke Park, the excitement of the crowds that throng Munster finals, the glamour of the great personalities that people the games, are only hinted at in the pages. Mick Mackey and Christy Ring get one mention each. The other giants of hurling and their counterparts in football must be read about in other publications. Kelly goes on to suggest that the work might have been entitled 'The G.A.A.: A Political History.'

There is much truth in the statement. In the introduction de Búrca attempts to sketch the historical and social background against which the rise of the G.A.A. must be seen. He sees the foundation of the G.A.A. as the continuation of an historical process, which began in the mists of history and stretched up through millennia to that historical date in Thurles in November 1884, when Irishmen began locating their sporting identity within the new association. Hurling, and at a much later date, Gaelic football, were part of the national expression for Irish people through the centuries. Hurling had an important place in the social life of pre-Christian Ireland as evidenced by the Brehon Laws. The game was part of what being Irish was and remained so until the coming of the Normans.

De Búrca shows how attitudes began to change then. Attempts were made to persuade or force the Irish to shed their racial distinctiveness. The Statute of Kilkenny legislated against hurling in 1367. Some time later 'Archbishop Colton of Armagh threatened excommunication for Catholics who played the 'reprehensible' game of hurling, since it led to 'mortal sins, beatings and ... homicides.' In 1527 the Statute of Galway also banned the game.

None of these attempts to kill hurling succeeded. There were further prohibitions of the game in the seventeenth century as in the Sunday Observance Act of 1695. But, as de Búrca reveals, many contemporary accounts and references establish that hurling was played all through the eighteenth century in many places. However, with the Great Famine in the middle of the nineteenth century, the games of hurling and football, which, de Burca shows, developed and flourished during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, began to decline.

According to de Búrca The Famine was not the only obstacle native games had to contend with in the last century. All over the country hurling and football were either discreetly discouraged or openly prohibited by government officials such as policemen and magistrates, as well as by some of the Catholic clergy and many landlords. The reasons given for such action varied from fear of violence and insobriety to suspicion of games being used as cover for meetings of various nationalist bodies.'

In the chapter dealing with the foundation of the G.A.A., de Burca expresses unqualified support for Michael Cusack and his role in the foundation of the G.A.A. 'To Cusack must go all the credit for starting the G.A.A.: without him there would have been no G.A.A., certainly not in the 1880s. He it was who supplied the inspiration and the driving force that led to its foundation.' He expresses the opinion that all his life Cusack's first allegiance was to Gaelic culture, rather than to political ideals. He found amateur athletics in Ireland in the hands of anglicised influences and was determined to wrench them into Irish control. There were other problems also. The standards in Dublin athletics had fallen and abuses had crept in. Money prizes were being commonly given to amateurs. Betting was widely tolerated. Handicaps were being framed to favour popular athletes. Much of the adult male population, including manual workers policemen and soldiers, was debarred from competing simply because its members were not gentlemen amateurs. Traditional events involving weights and jumping were often omitted from programmes in favour of ordinary races, which urban athletes had a better chance of winning.

In correspondence and discussions he argued for the restoration to athletic programmes of weight and jumping events, the lifting of the class barrier preventing the man-in-the-street from taking part in sports and the achievement of unity in the management of Irish athletics. From Pat Nally, the Fenian from Balla, Co. Mayo, de Búrca writes, Cusack took up the idea of wresting athletics from landlord control and bringing them under the control of nationalists. As a result he organised a National Athletic Meeting in Dublin to which artisans were invited. In a series of articles in the Irish Sportsman in 1881, Cusack argued the need for a controlling body for athletics in the country but insisted on the inclusion of nationalists in any such body, if it was to be genuinely representative of all Irish athletes.

De Búrca reveals how suddenly in 1882 Cusack switched his efforts from athletics to hurling with the foundation of the Dublin Hurling Club. Perhaps the reason was the existence in the city since 1870 of the University Hurley Club, which evolved into the Irish Hurley Union in 1882. Hurley was a debased form of hurling, a far cry from the robust form of the game Cusack had known in East Clare thirty years previously, and quite close to hockey. In these challenging circumstances Cusack decided to take steps to re-establish the national game of hurling, lest hurley should be passed off as the genuine article. Cusack started Saturday afternoon hurling practice sessions in the Phoenix Park.

In the summer of 1883 Cusack decided in effect to combine his two campaigns for the re-organisation of athletics on a democratic basis and for the revival of hurling. To this end he attended many rural sports meetings, especially in Munster, where he argued the case for Home Rule in athletics and for the inclusion of hurling in any new scheme. Later in the year he replaced the Dublin Hurling Club with the Metropolitan Hurling Club and resumed practice in Phoenix Park. Experienced hurlers from hurling areas began to attend the practice sessions. The club became Cusack's biggest sporting achievement 'til then. Founded to 'test the pulse of the nation', it satisfied him that, given encouragement and direction, public support for his ideas did exist.

The rest is history. The foundation meeting of the Gaelic Athletic Association was held in Hayes's Hotel, Thurles on November 1, 1884. A few weeks previously, in a letter to both United Ireland and the Irishman, Cusack succinctly put the case for a body such as that formed in Thurles subsequently. No movement aiming at the social and political development of a nation was complete unless it also provided for the cultivation and preservation of the nation's games. 'Because the recent athletic revival (a reference to the revival of amateur athletics in Ireland in the mid-1860s in Dublin) was sponsored by people of anti-Irish outlook, the ordinary citizen-was largely excluded from sport. Yet, although the management of sport was in non-national hands, most of the best athletes were nationalists; they should now take control of their own affairs.'

The foundation of the G.A.A. could, therefore, be described as a revolutionary movement. There were two elements involved. On the one hand athletics were being wrested from landlord and Unionist control and handed over to the plain people of Ireland, who were coming into their own for the first time. On the other hand the ancient game of hurling, and the less ancient game of Gaelic football, were being restored to their rightful place in the cultural life of the plain people of Ireland. The whole development was part of Cusack's desire to restore Irish culture to its rightful place in the lives of Irish people. Cusack had also been a pioneer of the Irish language movement and a founder member of the Gaelic League.

De Burca is at pains to show from his writings that Cusack envisaged that in sporting activities the G.A.A. would cross political and sectarian boundaries, as the Gaelic Union had already done in its work for the Irish language. Cusack invited no politicians to the foundation meeting. He asserted often that his dual object in starting the G.A.A. was to open athletics to the ordinary citizen and to halt and reverse the decline in Irish games.

Cusack's non-partisan policy and his desire to cross political and religious divides in his new organisation, had only limited success. During 1885 the growing conflict between the G.A.A. and the Irish Amateur Athletic Association (IAAA) on which body should represent Irish athletics gathered momentum. It was very difficult for the G.A.A., becoming identified with the Home Rule movement and the nationalist cause. Later the conflict developed within nationalism for the soul of the G.A.A. itself, between the Home Rule movement and the physical force camp, led by the secret oath-bound Irish Republican Brotherhood. The latter got control of the association in 1887 after Maurice Davin resigned from the presidency. According to de Búrca 'To at least some leaders of the LR.B. the G.A.A. must have seemed an ideal means of gaining by stealth the power they could not hope to win through the ballot box. The author describes the whole sorry mess in the middle of 1887: 'By mid-summer the G.A.A. presented a picture of growing disunity, with the two leading counties of Dublin and Tipperary in open revolt against what was regarded as the dictatorial regime of the Hoctor-dominated central executive, and with athletes in several areas considering transferring their allegiance to the rival IAAA. '

But, as this history clearly demonstrates, the G.A.A. survived these vicissitudes and those, which visited it during the Parnell split. The G.A.A sided with Parnell and became the target of strong opposition by the bulk of the clergy. It was infiltrated at all times by the current political ideas, was sometimes rent by deep divisions but at all times it came through.

De Búrca shows how the association reflected majority opinion in the immediate aftermath of the 1916 Rising. Accused by the Under-Secretary at Dublin Castle, Sir Matthew Nathan, of being anti-British, the G.A.A. issued a statement to the press in reply. According to the author, the main impact of this statement on the reader 'and undeniably the one intended by the central council of 1916, is of the Association's obvious desire to dissociate itself from the events in Dublin in Easter Week.' De Búrca goes on to say that the statement should be seen as a reflection of the climate of nationalist opinion generally in the period just after the Rising, the long-term effects of which nobody could then be expected to see.

The writer shows how the G.A.A. quickly changed its attitude towards the Rising as if reflecting the change in attitude among the general population. The association came under the dominant influence of the Sinn Fein members. Croke Park was the venue for the third annual convention of the Volunteers. A large body of G.A.A. men carrying hurleys, occupied a prominent position in the huge public funeral of Thomas Ashe. The G.A.A. added its voice in opposition to the British Government's decision in April 1918 to extend military conscription to Ireland. In fact, at the annual congress that year, held in private in the Mansion House, after an acrimonious debate the central council was censured for some contacts they made with the Castle authorities in 1916. (One of these contacts was a G.A.A. deputation to General Maxwell in November 1916 requesting him to put back the trains so that the attendance at G.A.A. finals would not suffer.) The debate ref1ected the dominant influence in the G.A.A. of the Sinn Fein members.

The change in G.A.A. attitudes is reflected in the part played by the G.A.A. in the War of Independence. The members were to the fore in the armed struggle and the foundation of the flying columns in the countryside came from fit, athletic members of the organisation. When the Civil War came along, with its obvious disruption of G.A.A. activities, it failed to split or unduly damage the association. In fact there is a strong case for arguing that G.A.A. members, who found themselves on opposing sides, did much to heal the divisions in Irish society caused by the fratricidal war.

According to Liam Kelly, in his review of the book already mentioned, 'The key point in the G.A.A.' s survival in the years 1884-1924 was loyalty. It engendered such loyalty among its membership that no matter how bitter the political or at times armed conflict, allegiance to the association was of prime importance.'

As already stated, the political side of the history of the G.A.A. is extensively treated. Another strength of the book is the treatment of the many personalities who contributed to the development of the association and to the making of the games of hurling and football the most popular in Ireland. Cusack has already been mentioned. De Búrca shows how Dick Blake, on his election as secretary, campaigned for a nonpolitical G.A.A. He lost no time in reforming the association. Within a month of his election the central council announced a revision of the constitution and rules. 'The old rule permitting political discussions at the annual convention was replaced; in its place came an explicit declaration that the G.A.A. was non-political and nonsectarian, a prohibition on the raising of political issues at G.A.A. meetings at any level, a ban on the participation by clubs in any political. movement and a recommendation for the avoidance of party names for clubs.' The author shows how such radical changes produced enemies and Blake's term of office came to a sudden end in 1898.

Another stalwart of the association who is well treated is James Nowlan. He came into power in September 1901 and with him, as secretary, Luke O'Toole. The former was to be president for twenty years, and the latter was to remain secretary for thirty years. According to de Búrca, they 'found the Association at the lowest point of its fortunes, were .to be instrumental in reviving it and guiding it to its first period of real expansion'.

O'Toole's successor, Pádraig O’Caoimh, who was to hold the office for thirty-five years, has his contribution put in order and perspective, as have all the men who helped shape and build the G.A.A. The purchase of Croke Park gets detailed treatment, as does the abolition of the 'Ban' in 1971

The author has compressed an immense amount of historical research into a relatively short book. It is well-written and well researched and documented. It a scholarly work and a very readable account even though the author shies away from the emotional and popular approach. It has a great clarity and precision of expression. Because it concerned itself with the weighty matters in the history of the association, it is open to criticism for its omissions. Mention has already been made of the sparcity of space devoted to players and games. Apart from the development of Croke Park there is little treatment of the development of other stadia in the country. It is surprisingly short on statistics; not even a list of the presidents and secretaries is made The cultural side of the association is passed over with little treatment of its work for the Irish language and latterly the place of Scór.

'The G.A.A.; A History' is ultimately a statement that events and decisions off the playing fields have been more lasting in their effects and more important to the association than the games of football and hurling that took place on the field of play. The book broke new ground and presented the first comprehensive history of the association as an organisation surviving the vicissitudes of many political takeover bids and growing from strength to strength.

A paperback edition of The G.A.A.: A History appeared in 1981. A shorter version of the book in Irish was published in 1984. An updated edition of the work, entitled The Story of the G.A.A. to 1990, was published by Wolfhound Press in 1990 for Irish Life Assurance plc. This work included a new cover and photographs not included in the original edition. In 1999 a second edition of the original work appeared. Published by Gill and Macmillan, it included a new cover and two additional chapters, one covering Games 1980-1999, the second Administration 1980-1999. It also included a one page bibliography and a professional index by Helen Litton.

Gaelic Games in Leinster (Comhairle Laighean C.L.G., 1984), 96 pp. Paperback.

This work on the history of the Leinster Council from the time it was set up in 1900, was a collaborative effort. Marcus de Búrca was the editor and he had the active cooperation of a special five-member history committee, which was set up in 1981. The members of the committee were Aodh O’Broin, Wicklow, Martin O'Neill, Wexford, Paddy Flanagan, Westmeath, Tom Ryall, Kilkenny, John Clarke, Offaly

The book can be divided into two halves with the first half devoted to a broad sweep of the province's history, and the second half to a statistical and photographic account. In the second section are to be found pen pictures of council chairmen and secretaries and the lists of winners of the many hurling and football competitions run by the council.

The first half of the book is the work of de Búrca. ln the course of five chapters he describes the beginnings of the council, taking the story to 1916 in chapter 1. He shows how the G.AA was strong in Dublin long before the formation of the council. Although Munster was the power-house of the early association, with six of the founders coming from that province, de Búrca states that 'geography alone dictated an important role for Leinster in the first 15 years or so of the G.A.A. In area and in population it was by far the biggest of the four provinces.

The author shows that by late summer 1900 unmistakable signs of pressure for reform of the G.AA had appeared. Leinster took a major part through the concerted action of prominent members in Wexford, Dublin and Kilkenny. Easily the most energetic advocate of reform was Walter ('Watt' ) Hanrahan of Wexford. In early August the Kilkenny and Wexford boards both threatened to leave the G.AA unless the central council took steps at once to ensure that it was run in a businesslike way. One of the reform ideas to come from Wexford chairman, Nick Cosgrave, was the idea of setting up provincial councils or committees to run their own championships. The motion to establish councils was passed at the 1900 congress, which was held in Thurles on September 9.

A meeting of representatives of Leinster counties on October 13 formed the Leinster Council. The first meeting adjourned to November 4 when a meeting of the Council elected James Nowlan, Kilkenny as chairman and WaIter Hanrahan as secretary. Since the Munster Council was not validly constituted until June 30, 1901. Leinster's was the first of the G.AA' s provincial councils. Those of Connacht and Ulster came in 1902 and 1903.

The author points out that in 1901 Nowlan was unanimously elected president of the G,A,A in succession to Deering, and another Leinster man, Wicklow's Luke O'Toole replaced Dineen as secretary. 'These two changes,' according to de Búrca, , marked the beginning of a new G.AA, determined to repair its badly run-down administrative machine and to put its finances on a sound basis.'

For de Búrca the provincial councils were to play an important party in the expansion of the G.AA in the years before 1916. 'They were to strengthen the administrative machinery of the Association and, through the provincial competitions which they would run, would generate new sources of income which would provide new funds for provincial development. By providing some degree of decentralisation they would also balance the growing trend in the early years of the century towards a Dublin-based G.A.A. In short they would act as the engine which would draw the Association into the second quarter of the century, when one of its most important periods of growth would take place.

The growth of the G.A.A. in Leinster is vividly illustrated in an income and expenditure table on page 25. For the year 1902-03 income was £640 and expenditure £410 leaving a surplus of £230. With the exception of 1916-17 the council had a surplus every year until 1922-23. For instance in the previous year the surplus was £1891. In the year 1925-26 the income was £3290. De Búrca states that the council finances were sound enough 'to permit another loan of £300 in January 1925 to allow the Central Council in install 20 modem turnstiles at Croke Park.

Officials played an important role in the development of the G.A.A. in the province. Walter Hamahan was a powerful figure in the early years and held the position of secretary until 1917. He was followed by John F. Shouldice, who was ten years in the office. A very influential figure, Martin O'Neill, succeeded in 1927 and was to remain in office until 1970. Three years earlier Bob O'Keeffe was elected chairman and was to remain in the chair until 1935. O'Neill and O'Keeffe formed a good partnership, which was to be largely responsible for the successes of the following decade.

The author shows that Leinster came through the Second World War unscathed. By the end of the 1940, all the main indicators of progress by the Leinster Council had improved beyond recognition on those at the start of the decade. 'Income in 1949 had more than quadrupled compared to 1940 and expenditure had more than trebled. The council's annual surplus had increased ten-fold and the number of affiliated clubs had risen by more than a third.'

The final chapter, entitled '25 Prosperous Years' covers the period 1960-1984. According to de Búrca 'the provincial administration managed to forge steadily ahead at a time when the Association as a whole was encountering major obstacles to progress. Largely through the introduction of the intermediate inter-county championships, the number of championship games played annually rose to new record levels. In football the province produced two new major contenders for national honours, Longford and Offaly. In addition, with Wexford's hurling resurgence continuing well into the late 1960s, the challenge of Leinster hurling to Munster's hitherto dominant position of the national game was further strengthened. De Búrca spends some time revealing the council's response to the Report of the G.A.A. Commission in 1971, which recommended the overhaul of the Association's structure. The council, through its secretary Ciaran O'Neill, expressed dismay at the move to centralise what he felt should remain a decentralised body. As evidence of the council's belief in the decentralised nature of the G.A.A., a decision was taken in 1965 to hold the annual provincial convention in future at a different venue in each of the twelve counties. The council also re-acted negatively to another initiative of the central council in 1968, to appoint a regional officer in each province. The duties of such an officer would include the promotion of the interests of the association in the province and ensuring that G.A.A. policy was vigorously pursued at all levels there. The proposal met with sharp criticism when it came before the council and was unanimously rejected.

Within its short span the book is a thorough presentation of the important features of the history of the Leinster Council. The author is diligent in the pursuit of facts and figures and gives a good account of the finances of the council. There is a balanced and rational approach to the story.

De Búrca, Marcus: One Hundred Years of Faughs Hurling- Fag-a-Bealagh (Faughs Hurling Club, 1985).

This is the story of one of the oldest hurling clubs in the country. Fag-a-Bealagh club, more popularly known all over Ireland as Faughs, came into existence in November 1885 in the academy of Michael Cusack himself and at his instigation, to provide competition for his own club, the Metropolitans. Apparently the decision to set up the club was taken as early as the Spring of 1885, at a meeting held in the Phoenix Park. Traditionally, Faughs was regarded as the second club to be established in Dublin. It came in ahead of the Michael Davitts Football Club, also formed in the month of November. In his secretary's report to the adjourned first annual congress of the G.AA, held in Thurles in February 1886, Cusack lists Faughs as the second of seven Dublin clubs affiliated. The name Faugh-a-Ballagh is an anglicised version of the old Irish battle-cry, 'Fag-a-Bealach', which may be translated as 'Clear the Way'.

The story of the Faughs is told largely through selected and edited contemporary press reports. In the Foreword to the book de Búrca acknowledges the help of members of the centenary committee of the club in collecting the raw material on which the book is based.

The book is divided into eight chapters with the first seven dealing the progress of the club in the Dublin hurling and football championships. The final chapter is devoted to miscellaneous activities in the club, such as handball, Scór, etc. It also includes a list of club officers and club captains. There is a selection of over sixty photographs, mostly of Faughs teams, the earliest being of the successful senior team that won four Dublin championships between 1900 and 1904.

The club was traditionally a haven for Tipperary hurlers based in Dublin and one of the fascinating features of the book are pen pictures of the giants of the Faughs club, especially in the early days. These make the most interesting reading and illustrate the strong Tipperary connection. Pat Cullen (1867-1939) from Loughmore was a member of the Dublin county board from 1887 and its treasurer from 1902. He won senior hurling titles with the Faughs between 1902-1904 and chaired the club between 1895 and 1907. Another Tipperary man was Danny McCormack (1876-1938) from Borrisileigh, who was on the Faughs 'four-in-a-row' team from 1900-1904, played for Dublin between 1905 and 1912, and was captain in 1907.

Other Tipperary players of note mentioned include Jack Cleary (1876-1948) Kilruane, Paddy Hogan of Horse and Jockey, who played for Dublin for many years, including the Dublin team against Tipperary in the 1906 All-Ireland senior hurling final, Jack Quane of the famous family of Tipperary footballers was a member of the Faughs football team that won the Dublin senior football championship in 1889, later emigrated to the U.S. and for many years a delegate from New York to the Central Council of the G.AA. Tim Gleeson (1877-1949) from Lisboney, Nenagh, Jack Connolly, from Ballypatrick, Thurles, who died suddenly in 1928 while refereeing a game in Parnell Park, Andy Harty (1880-1926), who held more posts at different levels in the G.AA. from 1903 to 1924 than any other official, Bob Mockler (1886-1966) a native of Horse and Jockey, who captained the Dublin team that won the senior hurling All-Ireland in 1920, Ned Wade of Boherlahan, who won minor and junior All-Irelands with Tipperary in 1930, joined Faughs in 1932, and played inter-county hurling for Dublin and Tipperary for the following fourteen years. Was unlucky in that he played for Dublin in 1937, when Tipperary won the All-Ireland, and played with Tipperary in 1938, when Dublin were successful, Jim Prior (1923-1980) of Borrisfleigh, who played on the Dublin senior hurling team from 1944 to 1957, losing two All-Irelands, to Waterford in 1948, and as captain to Cork in 1952, Charlie Downes of Roscrea, who was on the Dublin selection that won the 1938 AlIIreland, Mickey Williams of Cloughjordan and the famous Seamus Bannon.

I have referred only to the Tipperary players with the club. Faughs also attracted stars from other counties, like Jim 'Builder' Walsh and Terry Leahy from Kilkenny, Mick Gill from Galway, Harry Gray of Laois, and more. They were a very successful club and lead the Dublin hurling roll of honour with thirty senior titles, the last in 1992. Marcus de Búrca puts their achievement in perspective: 'This wholesale eclipse of the older hurling clubs serves only to emphasise the achievement of Faughs in the past quarter-century or more. Alone of the clubs founded back in the early days of the G.A.A, they have remained in the top rank in Dublin hurling. The Rapparees and Davis have long since vanished; Kickhams have not been in senior hurling for over half-a-century; Commercials after 90 years have yet to win a senior hurling title.

Michael Cusack and the G.A.A.

It was only logical that Marcus de Búrca should write a biography of Michael Cusack. In The G.A.A.: A History he had expressed his high admiration of the man from Carron, Co. Clare, who was solely responsible for the events leading up to the foundation of the G.A.A. in Thurles in November 1884. Of his dismissal twenty months after the foundation, de Búrca had this to say: 'No comparable case exists in modem Irish history of a national movement dismissing its founder within such a short time.'

When de Burca wrote The G.A.A.: A History, no biography of Cusack existed. In 1982 L. P. 0 Caithnia published Mícheál Cíosóg, a life of Cusack in the Irish language. The emphasis in the work was on Cusack as an Irish language enthusiast. No translation followed to make the book available to a wider audience. So there was a need for a biography that would give greater emphasis to Cusack's role in the foundation of the G.A.A. and the many other aspects of an extremely complex personality.

Marcus de Búrca was approached by Liam O’Maolmhichíl to do such a biography and this publication, which appeared in 1989, was the result. Less than two hundred pages long, the book is divided into eight chapters with about ten photographs. It also includes an index, and a list of Clare G.A.A. clubs, who subscribed to the publication. The main part of the work, as the title would suggest, is devoted to Cusack's G.A.A. life. In the first two chapters we learn of his boyhood in County Clare, his education and his life as a teacher. Starting as a primary teacher, he later moved into secondary and spent three years teaching at St. Colman's College, Newry. Until he started his own academy in Dublin in 1877, he led a peripatetic teaching existence that took him to the four provinces. In 1876 he married Margaret J. Woods in a Catholic service at Dromore.

According to de Búrca 'The ten years starting with the opening of his own school were the most important in Cusack's life. It was then that he made the decisions and took the actions for which he deserves to be remembered in modem Irish history. To be specific, between October 1877 and November 1887 he made his mark on Irish education, played a decisive role in Irish athletics, revived the national game of hurling, took part in a seminal move to revive the Irish language, edited a new Irish weekly news, and founded what has been for over a hundred years the biggest and most successful of Irish sports bodies.

The first major questions de Búrca addresses are how and why Cusack founded the G.A.A. He identifies three important events, which happened in 1882 that helped to shape the impact Cusack was to make on the Ireland of his time. The first of these was to force the newly founded Dublin Athletic Union to 'permit peelers, soldiers, labourers, tradesmen and artisans (excluded under the gentleman amateur rule) to compete at athletic sports. The second event was the opening of the National Industrial Exhibition in Dublin in August 1882. This exhibition was unique. It was entirely nationalist-controlled, its organisers refusing all official support or patronage. It made a deep and lasting impact on Cusack and five years later, in his own paper, The Celtic Times, he put the encouragement of native industry first among the four aims of the paper. The third event was his increased involvement in the Gaelic Union for the preservation and cultivation of the Irish Language. He became the most active committee member of the Union, which frequently met in his Academy. At his suggestion it commenced to hold Irish classes in a room provided in his Academy and under arrangements drawn up by him. The similarity between the title of the Union and the earliest title of the G.A.A. is obvious.

It was only a logical progression to the revival of Gaelic games. De Burca traces the developments that led to the revival of hurling. On the second last day of 1882 a small group of men, including Cusack, met in the College of Surgeons 'for the purpose of taking steps to re-establish the national game of hurling. ,xlix Five days later the same group with some others met to establish the Dublin Hurling Club. The setting up of this club was in response to the existence in Dublin for some years before 1882 of a game called hurley, an emasculated form of the traditional game of hurling. 'A glance at the twelve simple playing-rules of the DHC strongly suggests that Cusack had a major input into their drafting. While in some respects containing features one associates with hockey, in others they anticipate the rules of the game controlled by the G.A.A. from November 1884.

The Dublin Hurling Club didn't last very long and Cusack's interest in it waned quickly. Conflict developed between the supporters of hurling and hurley, as each side tried to poach players from the other. By October 1883 the affairs of the Dublin Hurling Club appear to have been wound up. De Búrca gives two reasons for the collapse. From the start the DHC failed to attract more than a handful of players. The failure to supply hurleys and balls may have been a reason. Initially there was an invitation from the DHC to join 'in the national movement'. Spectators to the sessions in the Phoenix Park began to join in the training sessions. However, this fraternisation was abruptly ended by a decision of the committee on 22 February to confine future matches to 'members, intending members and members of recognised clubs.'

The author concludes his chapter on the Dublin Hurling Club by stating that for nearly all those involved in the club, this was a once-only effort to revive hurling. 'The sole known exception was, of course, Michael Cusack, who only a few short months later, after the failure of the DHC, made yet another effort - this time almost single-handed, but this time too with much greater success. This was the foundation of the Gaelic Athletic Association in Hayes's Hotel, Thurles in November 1884.

The second major question examined by de Búrca is why, after only twenty months following the foundation meeting, the G.A.A. removed Cusack from his post as secretary. In a short review such as this it is not possible to trace the tangled web of plot and intrigue that led to the secretary's dismissal. De Búrca shows that two powerful men played a key role, Edmund Dwyer Gray, the proprietor of the Freeman's Journal and Archbishop Croke himself. Cusack himself contributed to his own demise. The bitterness of the war of words between the G.A.A. and the I.A.A.A. during 1885 had left its mark on the principal antagonists, not least on Cusask himself. 'Obliged to face his opponents alone in Dublin because his executive was largely scattered throughout the provinces, he became more dictatorial in his style of management and resentful of criticism from any quarter. In particular, he could not tolerate what he felt was lack of support from his own colleagues, some of whom now began to question his capacity to pilot the G.A.A. into calmer seas, or the wisdom of allowing him to do so.’

Unfortunately for Cusack his attack on the Freeman's Journal brought him into conflict with Archbishop Croke. Matters came to a head when Cusack concluded a letter to Croke with the blunt statement: 'As you faced the Pope, so I will, with God's help, face you and Gray. Croke's reply warned the G.A.A. of his intention to discontinue his patronage if Cusack was to be allowed to play the dictator in its councils, to abuse all who disagreed with him and to keep the Irish athletic world in perpetual feud.

The author shows how the forces against Cusack began to gather for the kill. An editorial in the Freeman's Journal put the case for Cusack's removal. 'He was always treading on someone's toes, suggesting ignoble motives, and only happy when quarrelling. If the G.A.A. did not quickly find a new secretary Cusack would wreck it. This was followed very quickly by a repudiation of Cusack's letter to Croke from McKay, one of Cusack's co-secretaries. Letters and statements from many clubs demanded Cusack's retraction. Cusack's manner was described as aggressive, insolent, dictatorial and an obstacle to the spread of the association.

The road to his dismissal was now clearly marked and de Búrca gives a vivid account of the three meetings, beginning on April 6, which brought about this result. Cuasck was willing to retract and apologise but the matter which brought things to a head was a proposal that all future communications made on behalf of the association should carry the names of the president and of two of the secretaries. It was Cusack's irrational response to this obvious attempt to silence him that was to cost him his post as secretary three months later.

When the meeting to consider Cusack's future as secretary began in Hayes's Hotel on July 4, some sixty-five delegates representing almost forty clubs were present. Not surprisingly, twenty-four of the clubs and almost half of the delegates were from Tipperary. Detailed allegations of incompetency against Cusack were presented. He was negligent in dealing with correspondence, failed to acknowledge affiliation fees received from clubs and hadn't issued medals for the previous season. One of the most damning allegations was that Cusack had pocketed some of the association's money.

According to de Búrca 'Cusack's defence ran on predictable lines. Regarding the unanswered correspondence, he argued that he had a complete answer in the restrictions imposed on him by the April meeting. Then, going on the offensive, he explained the conflicting views of Clancy (a member of the executive, who suggested the misappropriation of money) and himself on the purchase of trophies in such a way as to imply clearly that Clancy was guilty of improper behaviour. Finally, in a dramatic gesture of defiance, he answered the veiled accusations of embezzlement by producing a bundle of unanswered letters and uncashed cheques and throwing them all on the table in front of him.

The debate lasted four hours, becoming disorderly at times and being also punctuated by at least two walk-outs by Cusack. In the end, the case against him for neglect of his duties was almost unanswerable and Cusack was asked to resign because he had not discharged his duties as secretary. The voting was forty-seven to thirteen, an inglorious exit for a mall who had set up the organisation only twenty months previously. While de Búrca admits the adequacy of the case against Cusack, he firmly believes the manner of his dismissal was indefensible.

One of the great strengths of this book is the access the writer had to the Celtic Times, which appeared for the first time on January 1, 1887 and lasted for fifty-four weeks. It was the only paper of which Michael Cusack was in sole control. Not a single issue of this paper, the first of many periodicals which have been devoted to Gaelic games, had been seen by the public for at least fifty years from 1934 to 1984. Marcus de Búrca had access to an incomplete file of the paper (all but nine issues) while researching this book.

The paper reveals a new side of Cusack for long unknown, or at least only vaguely suspected from his other writings. 'The hidden Cusack was a man not only with a broad liberal approach to the economic and cultural development of his country, but also with a lively interest in social and labour problems both at home and abroad. It enables one to give a portrait of the founder of the G.A.A. largely unseen before, not available elsewhere, and not at all as unbalanced as one might have expected in the circumstances giving rise to the launching of the paper. It provides a new account of what was the most eventful year in the history of the G.A.A., from the pen of probably the most articulate and most observant side-line spectator. Finally, but by no means of least interest, it shows the Association's dismissed chief officer fighting back - making what was to prove his last bid to regain power in the body he himself had set up.'

Marcus de Burca has done a great service to the public with this biography of Michael Cusack. He has brought balance to the perception of a man, which was hung up on all the disagreeable aspects of his character, and he presents his subject as a multi-faceted character who always had the G.A.A. and Ireland as his primary concerns. He does not fail to show how Cusack himself was his own worst enemy and how he contributed significantly to his own downfall. At the beginning of this review of the G.A.A. writings of Marcus de Burca I stated that the library of books relating to the association at national level was a very small shelf De Burca's contribution to that shelf is significant and important. He has done a major service to the G.A.A. but also to the public at large.